I came across Maryse Condé recently via the Man Booker International Prize 2015 list of 10 nominated authors. She is third from the left in the picture below.

Not a book prize as such, it is an award conferred on an author who has a significant body of published work, regardless of the original language it was written in, though some of it must have been translated into English.

Not a book prize as such, it is an award conferred on an author who has a significant body of published work, regardless of the original language it was written in, though some of it must have been translated into English.

It is from such long lists the gems are found I say, and having read about all 10 thanks to this excellent Interview: The Finalists Speak in The Guardian, I spotted my potential winner immediately. A winner in the sense that I intend to read a few of their books. The Indian writer Amitav Ghosh was the only author I’d read on this list.

One writer jumped out at me straight away and I pursued her works with little consideration for the pending award result. Maryse Condé didn’t win the prize, the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai did, a writer whose books intellectuals rave about, but who I’m not sure I’m ready for yet.

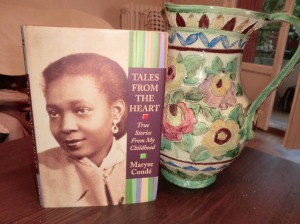

So I took Maryse Condé’s advice and started by reading this slim volume of essays of her childhood in Guadeloupe, Tales From the Heart, True Stories From My Childhood.

So I took Maryse Condé’s advice and started by reading this slim volume of essays of her childhood in Guadeloupe, Tales From the Heart, True Stories From My Childhood.

She takes us right back to the beginning, to the day of her birth. Being the youngest of 8 children, the family possessed an extended collective memory and she was fortunate to have heard the story of her birth from other perspectives.

Her appearance was both a source of pride and shame for her then 43-year-old mother and 63-year-old father, proud that her body remained robust enough to support the creation of a child and shame that it publicly displayed evidence of their continued indulgence in carnal pleasures.

The first chapter Family Portrait describes her parents relationship with France:

“For them France was in no way the seat of colonial power. It was truly the Mother Country and Paris, the City of Light that lit up their lives.”

World War II wasn’t considered dark on account of all the dreadful atrocities that occurred:

“but because for seven long years they were deprived of what meant the most to them, their trips to France.”

She recounts an anecdote of a waiter in a café complimenting the family on their excellent French pronunciation, to which her parents felt indignant, considering themselves just as French as a Parisian waiter, even more so because of their higher education, manners and regular travel.

Not understanding why it mattered so, she asked her brother Sandrino:

“Could he explain my parents behaviour?” to which he replied “Papa and Maman are a pair of alienated individuals,”

a mysterious word that would rest a long time in her consciousness until she came to understand it. She realised that not only did they take no pride in their African ancestry, they knew nothing of it, however:

“They believed they were the most brilliant and most intelligent people alive, proof positive of the progress achieved by the Black Race.”

In their neighbourhood all the mothers in their circle held a profession and with it contempt for the manual work they believed had been the undoing of their own mothers. They employed a servant who, though she raised 6 children of her own would begin work at 5am to take care of the needs of the family.

We meet her best friend Yvelise, two girls who did everything together, their friendship almost destroyed by the unfortunate intervention of one of her teachers, causing a temporary rupture.

Maryse’s mother Jeanne, knew the life she didn’t wish to lead, nor her children either, she had succeeded in breaking the cycle endured by her mother and grandmother and a good education was key (and perhaps being married to a successful and much older husband). Jeanne was a school teacher, revered and feared in equal measure by those around her. Her eldest son Sandrino and her youngest child Maryse the only two children who weren’t afraid to stand up to her, the others too terrified to challenge her.

On her birthday, her favourite pupils recited compliments, gave her roses, her husband bought her jewellery and the day would culminate with a family play, a short piece of theatre written themselves, in her honour.

‘Beneath her flamboyant appearance, I imagine my mother must have been scared of life, that unbridled mare that had treated her mother and grandmother so roughly…Both of them had been abandoned with their “mountain of truth” and their two eyes to cry with.’

10-year-old Maryse asked if she could read one of her compositions for her mother’s birthday.

‘I had no idea what I wanted to write. I merely sensed that a personality such as my mother’s deserved a scribe.’

If a book of essays can reach a crescendo, this is the moment when we reach it. The moment when Maryse learns that not all lessons come from one’s parents and school teachers, some come from life itself and often when we least expect it.

In the chapter School Days , she is at school (lycée) in Paris when her French teacher asks her to present to the class a book from her island. It is a watershed moment.

‘This well intentioned proposition, however, plunged me into a deep quandary. It was, let us recall, the early fifties. Literature from the French Caribbean had not yet blossomed. Patrick Chamoiseau lay unformed in his mother’s womb and I had never heard the name Aime Césaire. Which writer from my island could I speak about? I resorted to my usual source: Sandrino.’

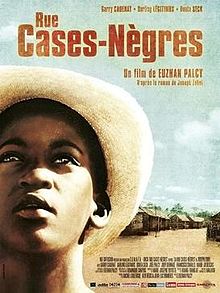

Sandrino introduces her to to a treasure. La Rue Case-Negres (Black Shack Alley) by Joseph Zobel and his hero José Hassan. It was made into an award-winning film titled Sugar Cane Alley.

It was her first introduction to a world no one up until that moment had ever mentioned; a world that highlighted slavery, the slave trade, colonial oppression, the exploitation of man by man and colour prejudice.

‘I was scared to reveal how José and I were worlds apart. In the eyes of this Communist teacher, in the eyes of the entire class, the real Caribbean was the one I was guilty of not knowing.’

These glimpses into the more significant and memorable aspects of childhood that shaped the author Maryse Condé are insightful, engaging and honest. Just as her consciousness is awakened, the vignettes finish and leave the reader desperate to know more.

I had intended to read this volume over time, but once I started reading I couldn’t stop, it is almost like reading a coming-of-age novella and at its conclusion, the writers fiction will begin. For Condé’s first novel Hérémakhonon is about a character raised in Guadeloupe, educated in Paris, who then travels to Africa in search of a recognisable past, just as she did.

‘Veronica has spent her childhood in Guadeloupe and, after a period as a student in Paris, wants to escape that island’s respectable black bourgeoisie, which she regards as secretly afraid of its own inferiority. She travels to an unnamed West African state and, while there, seeks an authentically African past with which she will be able to identify.’

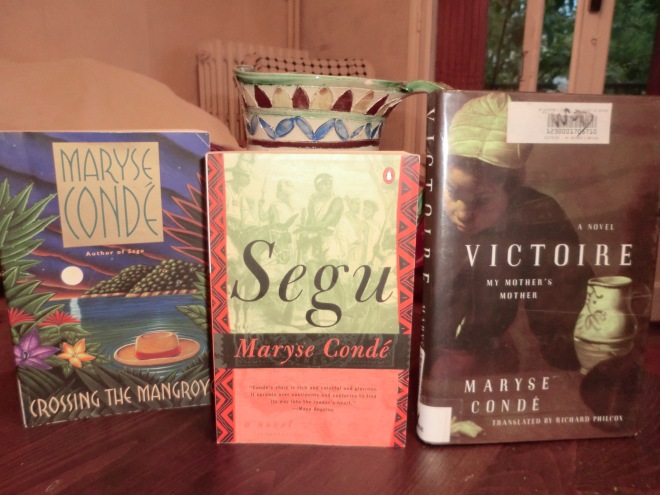

Tales From The Heart is an excellent read and an intriguing introduction to the writer and her influences and will certainly make you want to read more of her work. I am very happy I have these three novels on the shelf to follow-up with only I am missing that debut novel which I really want to read now too! Very highly recommended.

My Other Reviews

The Story of the Cannibal Woman

Click Here to Buy a book by Maryse Condé

This is really interesting. I certainly need to check out this writer. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy to have introduced her, I’m pleased to have discovered her too and look forward to reading some of her novels. We are fortunate so many have already been translated into English.

LikeLike

Sounds like an excellent recommendation – will look forward to reading this (preferably in the original if I can get it).

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad you found a copy, I am sure they are going to get snapped up quickly. I hope you enjoy it, I am sure you will, she is an interesting character in herself.

LikeLike

Checked this out on amazon, now ordered. Do you get commission :-)?

LikeLike

No, I’m not connected to any bookseller or publisher, I bought these books myself independently and was happy to find such a beautiful hardback copy, a real treasure. 🙂

LikeLike

Interesting, when I read your post on the Man Booker Prize, I was also interesting in her. Haven’t had a chance to get the books yet, but now I definitely will. As usual after I’ve read one of your wonderful reviews 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I take full responsibility for your pending enjoyment and bulging shelves! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol! As well you should! And I have loved each and every one of thise books too 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely review. This year’s International Booker longlist is certainly an embarrassment of riches. I’m just finishing Marlene van Niekerk’s magnificent epic Agaat, and have at least one title lined up from each nominee. For Condé the book I have in my wishlist is The Story of the Cannibal Woman. It also sounds very good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes the longlist is surely just the tip of an incredibly large iceberg of potentially great, relatively undiscovered in the English reading world, works. I’m glad they have introduced it and give it the time it deserves. I’ll have to look up that novel you’re intending to read now, such a great collection of work.

I look forward to reading about what you thought of Marlene van Niekerk’s Agaat too, thanks for your comment and sharing your epxerience of the list too.

LikeLike

Like you I first discovered Maryse through the International MB Prize and have her on my list of authors to explore – I really like the idea of reading Tales from the Heart first to get to know her then move on to her novels. Great review Claire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s great to know Poppy, I think these short essays are an excellent introduction to her writing and character, I can’t wait to read more.

LikeLike

You always come up with so many books for me to read. Thank you. (I haven’t been to Aix this season. Lets get together for coffee in the fall.)

Judy

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to that Judy, happy to hear you are enjoying all the book recommendations!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maryse Conde was the one author who jumped out at me when I read the Guardian piece as well. I’m glad to hear her novella worked so well for you. My curiosity has certainly increased after reading your post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you find something of hers to read too, I love discovering authors like this, with a rich backlist, just such a pity not to have come across her earlier.

LikeLike

My copy of “Coeur à rire …” arrived on my birthday – a lovely present to myself. Looking forward to reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoy! Such a beautiful collection.

LikeLike

Pingback: Victoire: My Mother’s Mother by Maryse Condé tr. Richard Philcox | Word by Word

Pingback: Women in Translation #WITMonth | Word by Word

Pingback: Top Reads 2015 | Word by Word

Pingback: Segu by Maryse Condé |

Pingback: Man Booker International Longlist 2016 #MBI2016 – Word by Word

Pingback: A Season in Rihata by Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe) tr. Richard Philcox #WITMonth – Word by Word

Pingback: Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys #ReadingRhys – Word by Word

Pingback: Reading Women in Translation #WITMonth – Word by Word

Pingback: The Story of the Cannibal Woman by Maryse Condé, tr. Richard Philcox #WITMonth – Word by Word

Oh my goodness. I feel like I have discovered a new favorite without having read any of her books yet.

Thank you for this post, for introducing me to her writings and I am going to get a copy of Tales From The Heart to start with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind words, you know, when I get a response like this, it’s almost like I haven’t read the book and it’s an excuse to go back and read my review and when I read it, I think, really, did I write all that. It really reminds me of the reason I write reviews, because there is so much joy and so many beautiful passages and insights we pick up when we read, which years later when we recommend a book to someone, we just know it’s great, but are unable to articulate in the same manner as we could have just after reading. So thank you for giving me the experience of going back and remembering that wonderful journey of reading Maryse Condé’s works.

I was just speaking about her to a friend yesterday and I couldn’t find the essays but I gave her Victoire to read, a book that Maryse Condé signed, as she came here to Aix en Provence about a year ago. She is almost blind now and her grandson had to guide her hand to where she should sign, but she was brilliant when speaking, so in command of her perspective. It was truly an honour to be in the audience. After years of living in Paris, she has now returned to Guadeloupe, but thankfully I still have a number of her books to read, I know I’m going to read them all.

LikeLike

Pingback: A Voice of Her Own: Maryse Condé wins Alternative Nobel Prize for Literature – Word by Word

Pingback: Top 10 Books by Women In Translation #100BestWIT – Word by Word

Pingback: Top Five Memoirs #StayAtHome – Word by Word

Pingback: Crossing the Mangrove by Maryse Condé (1995) – Word by Word

Pingback: International Booker Prize Longlist 2023 – Word by Word